Curiosity Project

21st Century Competencies

Ministry of Education, Singapore

One of the most happy, surprising, unexpected occurrences of this project came in the form of a report from the Ministry of Education, Singapore, titled 21st Century Competencies.

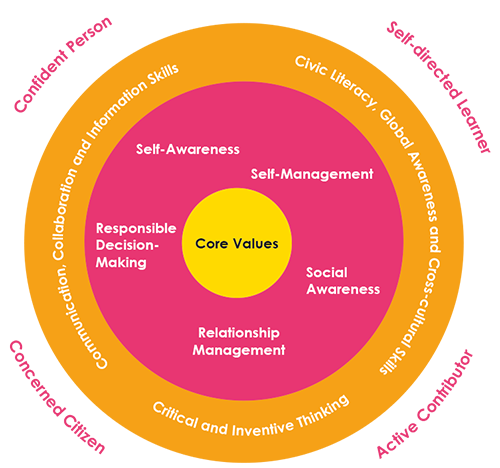

At the heart of the Ministry of Education's framework is the belief that knowledge and skills without solid values are not enough, that values "shape the beliefs, attitudes and actions of a person, and therefore form the core of the framework."

From the core, the framework expands to signify Social and Emotional Competencies, described as "skills necessary for children to recognize and manage their emotions, develop care and concern for others, make responsible decisions, establish positive relationships, as well as handle challenging situations effectively." These are echoes of the traits valued in Academic Tenacity and Academic Mindsets, but with a somewhat less moralizing tone.

The Ministry of Education conceives of the outer ring of the framework as directly related to competencies necessary to live and function in a globalized society. This manifests in a focus on: civic literacy, global awareness, and cross-cultural skills; critical and inventive thinking; and communication, collaboration and information skills.

I note that these competencies are relatively similar to many of the Core Outcomes established at Portland Community College. Further, the combination of "critical and inventive thinking" and "collaboration and information skills" speak pretty directly to competencies that one seeks to develop through Maker Education, and that are highly valued in design-thinking. For these reasons, this framework has become among the most useful for me in thinking about how to know if I am "covering it" while trying to clear obstructions to creativity and curiosity in the library research environment.

Student Outcomes

The Ministry of Education proposes that a student educated in this system should emerge with a "good sense of self-awareness, a sound moral compass, and the necessary skills and knowledge to take on the challenges of the future." In short, what Perkins would call a person with lifeready learning under her belt.

While the Ministry of Education values some things that may feel less applicable to an American collegiate environment, their ultimate summation of Student Outcomes is pretty spot on:

- a confident person who has a strong sense of right and wrong, is adaptable and resilient, knows himself, is discerning in judgment, thinks independently and critically, and communicates effectively.

- a self-directed learner who questions, reflects, perseveres and takes responsibility for his own learning.

- an active contributor who is able to work effectively in teams, is innovative, exercises initiative, takes calculated risks and strives for excellence.

Note how these resemble some of the more positive descriptions of a student who has Academic Tenacity, or has accomplished "deeper learning" (as established by the Deeper Learning MOOC).

Sternberg

Robert J. Sternberg

Sternberg, R. J. (2010, October 10). Teach creativity, not memorization.

Retrieved from http://chronicle.com/article/Teach-Creativity-Not/124879

In his 2010 commentary piece for The Chronicle of Higher Education, Sternberg takes a hard look at at what he calls the "archaic notion of what it means to be intelligent." In order to address the over-reliance on traditional admissions procedures, which rely on standardized testing, and generally select for "a specific kind of cognitive and memorization-based intelligence," Sternberg has developed Project Kaleidoscope, designed to select candidates based on wisdom, creativity, and practicality.

Now that we've begun to let in students with a wide range of abilities, Sternberg notes that we need to teach them in ways that reflect how they learn. To this end, he proposes 12 methods of encouraging creativity in the classroom:

- Redefine the problem

- Question and analyze assumptions

- Teach students to sell their creative ideas

- Encourage idea generation

- Recognize that knowledge is a double-edged sword

- Challenge students to identify and surmount obstacles

- Encourage sensible risk-taking

- Nurture a tolerance of ambiguity

- Foster self-efficacy

- Help students find what they love to do

- Teach importance of delaying gratification

- Provide an environment that fosters creativity

A large part of the article seems to be speaking to the notion of agency: "Many students have ideas that are creative with respect to themselves but not to a field. I tell my own students that the teaching-learning process goes two ways. I have knowledge they do not have, but they have a flexibility I do not have -- precisely because they do not know as much as I do. By learning from -- as well as teaching -- our students, we can open channels for creativity." I'm still working on how to put together Sternberg's thoughts with the Agency by Design working coming out of Harvard.

Overall, I find the 12 methods proposed by Sternberg to be practical, although I recognize that each will be different to implement within the disparate disciplines, subjects, and programs at PCC. Perhaps, taken as written, they lay out a map to accomplish greater agency in the classroom, and needn't be adopted all at once. Of the 12, I would suggest that picking 3-4 to work on in a single year would be a sizeable (but manageable) undertaking.

Connections: To connect to a familiar and traditional educational model, Sternberg is essentially proposing that we shift our conceptualization of education away from the bottom three elements of Bloom's Taxonomy (remember, understand, apply) and toward the top three (analyze, evaluate, create). There is much debate among educators as to the intent of the taxonomy and whether the bottom half is meant as a scaffold to the top. This debate has lead to several revisions of the taxonomy. Sternberg's questions and theorizing fit right in line with those revisions.

Questions: From a library and research perspective, memorization-based intelligence (which Sternberg argues we've been privileging for far too long) reinforces memory as more highly-valued than creativity. Creativity allows more room for failure and for learning from failure (iterative failure/success is a huge part of the research process). What does admitting students with a wide range of abilities and teaching them in ways that reflect how they actually learn mean for a community college? How do our teaching methods compare with (and differ from) the traditional types of intelligence reinforced in the classrooms that Sternberg references?

Deeper Learning

Deeper Learning

There have been some efforts to envision what putting all of these things together would look like. What would it mean to attain a state of deeper learning, with mastery of content and a sense of purpose.

- Mastering content

- Critical thinking

- Effective written and oral communication

- Collaboration

- Learning how to learn

- Developing academic mindsets

If deeper learning is the ultimate goal, can it be taught? To a certain degree. But for educators to engage in deeper learning with students, researchers say they must begin with clear goals and let students know what’s expected of them. They must provide multiple and different kinds of ideas and tasks. They must encourage questioning and discussion, challenge them and offer support and guidance. They must use carefully selected curriculum and use formative assessments to measure and support students’ progress.

-

Beyond Knowing Facts, How Do We Get to a Deeper Level of Learning?On deeper learning and cultivating academic growth mindsets.

Perkins - Six Beyonds

Perkins,senior co-director of Harvard's Project Zero, is another scholar I had the pleasure of rubbing elbows with while on leave. He's been grappling with what to do with the student who raises her hand and asks, "Why do we need to know this?"

been grappling with what to do with the student who raises her hand and asks, "Why do we need to know this?"

Despite labeling it an “uppity version of one of the most important questions in education, a question with only three words: What’s worth learning in school,” Perkins acknowledges that for educators it's generally hard to come up with a compelling answer. Most answers sound something like a thinly-veiled "because I have to teach it to you."

In his writing about this topic, Perkins encourages us to explore concepts he has labeled "lifeworthy learning” and “lifeready learning." Lifeworthy and lifeready learning, according to Perkins, come from educational experiences which yield learning we can apply throughout our lives. Lifeworthy learning is learning that is "likely to matter in the lives learners are likely to live" whereas lifeready learning "ready to pop up on appropriate occasions and help make sense of the world."

"Without the right sort of teaching and learning, content lifeworthy in principle can turn out not at all lifeready in practice," says Perkins. How do we get to the right sort? We go beyond...

- Beyond content

- Beyond local

- Beyond topics

- Beyond traditional disciplines

- Beyond discrete disciplines

- Beyond prescribed studies

To achieve learning that is lifeworthy and lifeready, Perkins suggests four quests:

- Identify lifeworthy learning in contrast with not-so-lifeworthy learning

- Choose what lifeworthy learning to teach from the many possibilities

- Teach for lifeworthy learning in ways that make the most of it

- Construct a lifeworthy curriculum

Coining the phrase “expert amateurism," Perkins suggests that educators should “build expert amateurism more than expertise” in their students, because "the expert amateur understands the basics and applies them confidently, correctly, and flexibly.” The premise being that students need to master the fundamentals of learning and then decide where they want to specialize. This approach helps assure that individuals have flexibility as well as specialty when it comes to knowledge and skills. Much of Perkins' work is directly tied to the notion of 21st Century Competencies, although he tends to really hone in on specific competencies.

Questions: What do you teach that is worth learning? How do you know it's worth learning - does that feedback come from scholars, students, prospective employers? (how) Do academic librarians differ in their approach to providing lifeworthy and lifeready learning opportunities?

Connections: In the vein of lifeworthy learning, some publications from Project Information Literacy that may help shed light on what students and prospective employers consider "lifeworthy" learning.

Head, A. J., & Eisenberg, M. B. (2011). How college students use the Web to conduct everyday life research. First Monday, 16(4).

Head, A. J. (2012). How college graduates solve information problems once they join the workplace. Project Information Literacy Report.

Head, A. J., Van Hoeck, M., Eschler, J., & Fullerton, S. (2013). What information competencies matter in today’s workplace?. Library and Information Research, 37(114), 74-104.

Academic Mindsets/Tenacity/Grit

Academic Mindsets

Carol Dweck

Academic mindsets are

- I belong in this learning community

- I can change my abilities through effort

- I can succeed

- This work has value and purpose for me

Academic Tenacity

Dweck, Walton, Cohen

An academically tenacious student:

- Belongs academically and socially

- Sees school as relevant to their future

- Works hard and can postpone immediate pleasures

- Is not derailed by intellectual or social difficulties

- Seeks out challenges

- Remains engaged over the long haul

Grit

Although Angela Duckworth of UPenn coined the term grit, the concepts of academic tenacity and grit are very closely related. It feels irresponsible to discuss tenacity and growth without discussing the inherently complicated (and popular) notion of academic grit.

NPR - Does Teaching Kids To Get 'Gritty' Help Them Get Ahead? [transcript]

NPR - On The Syllabus: Lessons in Grit

Connections: There are a lot of scholars (and current and former students) debating the merits of the concept of academic grit. The following are a list of places to read more on the problematic narrative around grit.

Alfie Kohn

-

Why Self-Discipline Is Overrated: The (Troubling) Theory and Practice of Control from Within

-

The Downside of “Grit”: What Really Happens When Kids Are Pushed to Be More Persistent?

- Ten concerns about the ‘let’s teach them grit’ fad

Katie Osgood

Radical Scholarship (blog)

But the greatest failure of the NPR look into "grit" is what, once again, is missing: Not a single mentioning of race, of the strong critical rejection of the "grit" narrative as a not-so-thinly masked appeal to racism.

"Grit"is a mask, a marker for privilege and slack that suggests people who succeed do so because of their effort (and not their privilege and the slack of their lives) and that people who fail do so because of a failure of character (and not due to the scarcity that overburdens them).

The "grit" narrative is essentially a whitewashing of the power of privilege as that is a product of lingering racism.

-

Misreading “Grit”: On Treating Children Better than Salmon or Sea Turtles

-

Learning and Teaching in Scarcity: How High-Stakes ‘Accountability’ Cultivates Failure

-

An Open Apology, with Explanations: Math, Behaviorism, and “Grit”

Ira Socol

curiosity - confidence - courage

Joan Goodman

Goodman differs from some of the other models available in that she doesn't propose that grit is inherently related to the process. Rather, she presents the notion that curiosity, confidence, and courage run together in an ongoing cycle, of which grit is sometimes a byproduct. This is a positive addition, in that it suggests that one needn't teach to the notion of creating "gritty" students, but rather one should clear obstacles to curiosity. Once the student has the change to engage her curiosity, her confidence will grow. With a growth in confidence, one becomes courageous enough... to change application, to try something bigger, to engage in things that may create grit.

Dan Pink

Dan Pink was one of the most surprising stops in my research tour. I didn't expect to find myself delving into business strategies around motivating employees. Fundamentally, as my journey convinced me, students aren't broken, how we teach is broken. That I spend a tremendous amount of time working with students who can't decide on something to be interested in tells me that there's also some critical work to be done around the area of motivation.

Dan Pink fits in well here because he has spent a significant amount of energy looking at over forty years of scientific research that tells us how motivation works - and has come to the conclusion that organizations repeatedly do the opposite of what science indicates. Schools rank high among these organizations with mismatched approaches to motivation. In his book Drive, Pink digs into how we could be doing a better job of organizational motivation and comes to the conclusion that it all hinges on autonomy, mastery, and purpose.

As Amy Azzam noted in her conversation with Dan Pink, people tend to rely on external rewards to get kids (students) to do something. Pink's take on this is what he says 50 years of behavioral science tells us: if/then motivators ("If you do this, then you get this") can be effective for "simple, short-term, algorithmic tasks." These types of rewards are not powerful motivators for more complex or creative tasks.

Schools tend to rely heavily on if/then systems of reward for everything. This is a problem.

Pink finds that offering people a prize, a reward, does get their attention - but their attention is captured in a very narrow way. People do not achieve the same levels of success when working on a task requiring creativity and critical thinking when they approach from a very narrow perspective.

When talking about education, Pink says that we need to pay more attention to the distinction between performance goals and learning goals. A performance goal is "I want to get an A." A learning goal says, "I want to master this subject." Research by Carol Dweck and others shows that single-mindledly focusing on and achieving a performance goal does not indicate learning. In short, the student "is less likely to retain what she learned to get the A, less likely to persist when the going gets tough, and less likely to understand why" the subject is important in the first place.

By contrast, Pink says, single-mindedly focusing on a learning goal (mastering algebra, for example) creates a good likelihood that the student will also achieve the performance goal. Conclusion? It's best to pursue the learning goal and use grades and scores as feedback mechanisms as the student works toward mastery.

While this all made great sense, I found myself dismayed to be returning to the scene of the grit crime, as I'd come to think of it. What Pink provided were other ways to consider how students might find that place of persistence, of academic tenacity, rather than the moralizing undertones provided by Duckworth in her foundational work on "grit".

Pink suggests that ultimately people need autonomy to grow, whereas most schools are environments of compliance. It's not that teachers value compliance most, teachers generally value engagement. All the same, educational organizations are places where students (and teachers) are expected to comply, above all else. Want to increase engagement rather than compliance? Pink says you have to increase the degree of autonomy that people have over what they do, by the right amount at the right moment.

What it means in terms of students is giving them some discretion over what they study, which projects they do, what they read, or when or how they do their work - just upping the autonomy a bit. We're not talking about a wild and wooly free-for-all where everyone does whatever they want whenever they want to do it.

Pink is a big proponent of the idea that turning work into play increases opportunities to build mastery. As with his approach to autonomy, Pink says the trick is to find the "Goldilocks" tasks, the learning activities that are not too hot or cold, but are "just right."

In addition to getting the tasks just right, we also need to pay more attention to the "why" of it all. Research, Pink says, shows that people do better at a task if they know why they are doing it. An educational system overly focused on compliance (the "how" of doing things) is not likely to simultaneously be focused on getting at the why of things. Understanding the "why" of something often relates to the notion of purpose. If the student can see a subject (algebra) as attached to a cause that is bigger than herself, she can begin to develop a sense of satisfaction, of purpose.

If a student were to ask you why she is asked to learn a specific element of your course, can you give a thoughtful, narrative answer that speaks to purpose?

If you can't, should you still be teaching it?

Finally, Pink suggests that teachers could stand to learn a lot more about selling. We need to sell the value of education to students. More on this in his book To Sell is Human.

-

Drive by Daniel H. Pink

ISBN: 9781594484803Publication Date: 2011-04-05 -

To Sell Is Human by Daniel H. Pink

ISBN: 9781594487156Publication Date: 2012-12-31

- Last Updated: Feb 17, 2023 2:36 PM

- URL: https://guides.pcc.edu/curiosity

- Print Page